If you’ve ever considered brewing your own beer at home, you’re in for a treat. But before you embark on this exciting journey, it’s important to familiarize yourself with the essential lingo of homebrewing. From mash tun to fermentation, this comprehensive glossary will guide you through the A-Z of homebrewing terms, ensuring that you’re well-equipped to create your own delicious craft beers. Whether you’re a seasoned pro or a complete beginner, this guide is a must-read for anyone looking to delve into the world of homebrewing. So grab a cold one, sit back, and get ready to expand your beer knowledge like never before!

A

Adjuncts

When it comes to homebrewing, adjuncts refer to any additional ingredients apart from the four main ingredients of beer – water, malt, hops, and yeast. These adjuncts can be used to enhance the flavor, color, or aroma of the final brew. Common adjuncts include oats, corn, rice, fruits, herbs, spices, and even coffee or chocolate. They offer homebrewers the opportunity to experiment and create unique and interesting brews by adding layers of complexity to the beer.

Alcohol by volume (ABV)

ABV is a term used to measure the alcohol content in a beverage, including beer. It represents the percentage of alcohol present in relation to the total volume of the drink. ABV is an important factor to consider when brewing at home, as it affects the strength and potency of the beer. Different beer styles have varying ABV ranges, from low-alcohol session beers to high-octane imperial stouts. By understanding and controlling the ABV of your homebrew, you can ensure that you’re creating a beer that meets your desired taste and strength.

All-grain brewing

All-grain brewing is a method of brewing that involves using malted grains as the primary source of fermentable sugars. In this process, the brewer mashes the malted grains, usually a combination of barley, wheat, rye, or other grains, to extract the sugars needed for fermentation. This technique allows for greater control over the flavor profile of the beer, as the brewer has more flexibility in choosing and manipulating different malt varieties. All-grain brewing is often considered the next step for homebrewers looking to expand their skills and create more complex and unique beers.

Attenuation

Attenuation is a term used to describe the extent to which yeast ferments the sugars in the wort during the brewing process. It measures the percentage of sugars that are converted into alcohol and carbon dioxide by the yeast. High attenuation means that the yeast has consumed a significant amount of sugars, resulting in a drier and less sweet beer, while low attenuation leads to a sweeter and maltier beer. Understanding and manipulating attenuation is crucial for achieving the desired level of sweetness and body in your homebrew.

B

Bitterness

Bitterness is an essential characteristic of beer, balancing out the sweetness of the malt. It is primarily determined by the hops used during the brewing process. Hops contain bittering compounds that are released during boiling, adding a bitter flavor to the beer. Bitterness is measured in International Bitterness Units (IBU), which represents the concentration of bitter compounds in the beer. Different beer styles have varying levels of bitterness, ranging from crisp and refreshing lagers with low IBUs to hop-forward and bitter IPAs with high IBUs.

Boil

The boil is a critical step in the brewing process that involves heating the wort to a rolling boil. During the boil, various chemical reactions occur, including isomerization of hop compounds, sterilization of the wort, and evaporation of unwanted compounds. The length and intensity of the boil can affect the flavor, aroma, and stability of the final beer. Generally, a boil of 60 to 90 minutes is recommended, but it may vary depending on the beer style and recipe.

Bottle conditioning

Bottle conditioning is a method of carbonating beer naturally within the bottle. After fermentation is complete, a small amount of sugar or a specific type of yeast is added to the beer before bottling. This additional sugar or yeast ferments in the sealed bottle, producing carbon dioxide, which carbonates the beer. The bottles are then stored for a period of time to allow the carbonation process to occur. Bottle conditioning can add complexity to the beer’s flavor profile and produce a natural and lively carbonation.

Brew kettle

The brew kettle, also known as the boiling kettle, is the vessel used to boil the wort during the brewing process. It is typically made of stainless steel or other heat-resistant materials. The brew kettle must be large enough to accommodate the volume of the wort and allow for vigorous boiling without boiling over. The kettle may also include features such as valves, thermometers, and sight gauges to help monitor and control the brewing process. A well-designed brew kettle is essential for achieving a successful boil and extracting the desired flavors from the hops.

Bright beer

Bright beer refers to beer that has undergone clarification and is ready for packaging or serving. It is called “bright” because it appears clear and has a polished appearance without any visible sediment or haze. The clarification process involves removing any suspended particles or haze-causing compounds from the beer, resulting in a visually appealing and stable product. Bright beer can be bottled, kegged, or served directly from the conditioning vessel, depending on the brewer’s preference.

C

Carbonation

Carbonation refers to the presence of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the beer, which produces the bubbles and effervescence commonly associated with beer. Carbonation can occur naturally, through bottle conditioning or secondary fermentation, or artificially, by force carbonating the beer using carbon dioxide gas. The level of carbonation can greatly impact the perceived mouthfeel, aroma, and flavor of the beer. Achieving the right level of carbonation is crucial to ensuring that the beer is enjoyable and refreshing to drink.

Clarification

Clarification is the process of removing any haze-causing particles or suspended solids from the beer, resulting in a clear and visually appealing final product. There are various methods of clarification, including using fining agents such as gelatin or Irish moss, filtration, or time for the particles to settle. Clarification is important for improving the beer’s appearance and stability, as well as enhancing the flavors and aromas by allowing them to shine through without interference from suspended particles.

Cold crash

Cold crashing is a technique used during the brewing process to help clarify the beer and improve its stability. It involves lowering the temperature of the fermenting beer to near-freezing temperatures, typically around 32 to 40 degrees Fahrenheit (0 to 4 degrees Celsius). This extended period at a cold temperature causes any remaining suspended particles or yeast to settle to the bottom of the fermentation vessel. Cold crashing can help create a clean and bright beer, free from any hazy or cloudy appearance.

Conditioning

Conditioning, also known as maturation, is the period after fermentation when the beer is allowed to rest and mature. During this time, the flavors of the beer continue to develop and harmonize, while any remaining undesirable off-flavors are reduced. Conditioning can take place in a separate vessel, such as a secondary fermenter or conditioning tank, or in the same vessel used for primary fermentation. The duration of conditioning varies depending on the beer style and desired flavor profile, ranging from a few weeks to several months.

Dry hopping

Dry hopping is a technique used to enhance the aroma and flavor of beer by adding hops during or after fermentation. Unlike hops added during the boil for bitterness, dry hops are added when the beer is at a cooler temperature, typically around 60 to 70 degrees Fahrenheit (15 to 21 degrees Celsius). This process allows the hops to impart their aromatic oils without contributing significant bitterness. Dry hopping can provide a burst of fresh hop aroma, ranging from citrus and floral notes to pine and tropical fruit flavors, depending on the hop variety used.

D

Degassing

Degassing is the process of removing any excess carbon dioxide from the beer before bottling or kegging. Excessive carbonation can lead to over-pressurized bottles or foamy pours, so degassing is essential to ensure the beer is properly carbonated and easy to pour. There are various methods of degassing, including gently stirring or agitating the beer to release the trapped carbon dioxide or using specialized equipment such as a degassing wand or vacuum pump. Removing excess carbon dioxide allows the true flavors and aromas of the beer to be experienced without interference from excessive carbonation.

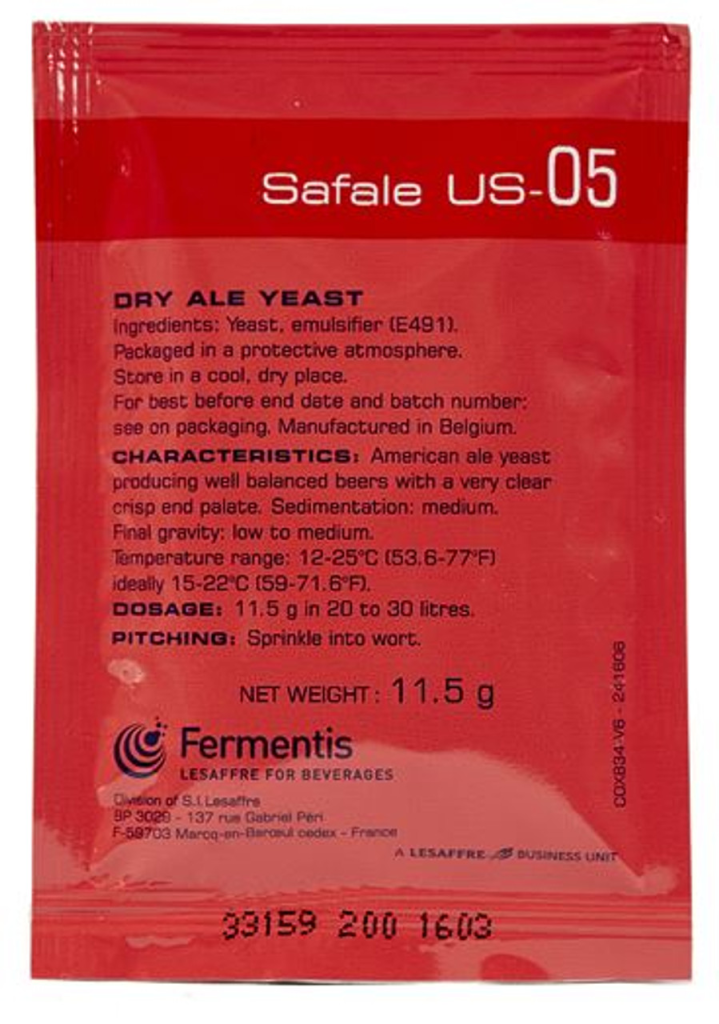

Dry yeast

Dry yeast is a type of yeast that has been dehydrated and packaged into small granules or pellets. It is a popular choice among homebrewers due to its long shelf life, ease of use, and wide availability. Dry yeast can be stored at room temperature, making it convenient and cost-effective. It is important to rehydrate dry yeast properly before pitching it into the wort to ensure optimal yeast activity and a successful fermentation. Dry yeast comes in various strains, allowing homebrewers to choose the most suitable yeast for their beer style and flavor preferences.

E

Extract brewing

Extract brewing is a method of brewing that utilizes liquid or dry malt extract as the primary source of fermentable sugars. This approach is often favored by beginner homebrewers or those with limited equipment or time. The malt extract is derived from mashing and boiling malted grains, and it provides a convenient and concentrated form of fermentable sugars. By using malt extract, homebrewers can create flavorful and well-balanced beers without the need for mashing grains, reducing the overall brewing process’s complexity.

Esters

Esters are volatile compounds produced by yeast during fermentation that contribute to the beer’s aroma and flavor. These compounds lend fruity or floral characteristics to the beer, such as banana, pear, apple, or apricot aromas. Esters are influenced by various factors, including yeast strain, fermentation temperature, and the presence of certain adjuncts or compounds. While esters can add depth and complexity to a beer’s profile, excessive ester production can lead to off-flavors or an imbalance in the final product. Understanding and controlling ester production is essential for achieving the desired flavor profile in your homebrew.

F

Fermentation

Fermentation is a crucial step in the brewing process where yeast converts the sugars in the wort into alcohol and carbon dioxide. During fermentation, yeast consumes the fermentable sugars, producing ethanol and carbon dioxide as byproducts. This process typically takes place in a fermentation vessel equipped with an airlock to allow carbon dioxide to escape while preventing oxygen or contaminants from entering. Fermentation can take anywhere from a few days to several weeks, depending on the beer style, yeast strain, and fermentation temperature. It is during this stage that the flavors and aromas of the beer develop, giving it its unique character.

Fermenter

The fermenter, also known as the fermentation vessel or primary fermentor, is a container used to hold and facilitate the fermentation process. It can be made of various materials, such as food-grade plastic, glass, or stainless steel, and is designed to be airtight and easy to clean and sanitize. The fermenter should have enough capacity to accommodate the entire volume of wort, leaving enough headspace for the krausen, the foamy layer of yeast, and proteins that form on top during fermentation. It is important to choose a proper fermenter that suits your needs and preferences, considering factors such as capacity, insulation, and ease of use.

Flocculation

Flocculation refers to the tendency of yeast to clump together and settle at the bottom of the fermentation vessel after fermentation is complete. Yeast strains exhibit different levels of flocculation, ranging from highly flocculent, where yeast settles quickly and compactly, to low flocculation, where yeast remains suspended in the beer for longer periods. Flocculation can impact the clarity and stability of the beer, as well as its flavor and aroma. Understanding the flocculation characteristics of a particular yeast strain is essential for achieving the desired clarity and appearance of the finished beer.

G

Grain bill

The grain bill refers to the combination and proportion of different grains used in brewing beer. It typically consists of malted barley as the base grain, but other grains such as wheat, rye, oats, or corn can be included to add flavor, texture, or brewing characteristics to the beer. The composition of the grain bill greatly influences the color, flavor, body, and mouthfeel of the final product. Homebrewers have the flexibility to experiment with different grain combinations to create unique and flavorful beers.

Gravity

Gravity, also known as specific gravity, is a measurement used in brewing to assess the density of the wort or beer. It indicates the concentration of sugars and other dissolved compounds in the liquid. Gravity is typically measured using a hydrometer or refractometer and is expressed as a numerical value, such as 1.050. The difference in gravity before and after fermentation can help determine the alcohol content of the beer, as yeast consumes the sugars, leading to a decrease in gravity. Understanding gravity is essential for tracking fermentation progress, estimating alcohol content, and achieving consistency in your homebrew.

Green beer

Green beer is a term used to describe beer that is still relatively young and undergoing the maturation process. It refers to beer that has not yet fully developed its intended flavors, aromas, and textures. Green beer can taste or smell “raw” or unbalanced, with flavors that may mellow or change over time. Proper conditioning and aging can transform green beer into a more refined and desirable brew. It is important to exercise patience and allow the beer to mature properly before judging its final qualities.

H

Heating element

The heating element is a crucial component in electric brewing systems that provides the energy required to heat the water and boil the wort. It can come in various forms, such as electric heating elements, gas burners, or even induction cooktops. The heating element should be capable of reaching and maintaining the desired temperatures throughout the brewing process. It is essential to choose a heating element suitable for your brewing setup, considering factors such as power output, energy efficiency, and safety.

Hopback

A hopback is a piece of equipment used in the brewing process to infuse additional hop flavor and aroma into the beer. It is a vessel or chamber placed between the brew kettle and the fermentation vessel and is filled with whole hops. As the hot wort passes through the hopback, it extracts volatile oils and aromatic compounds from the hops, adding depth and character to the beer. Hopbacks can be either open vessels or enclosed chambers, depending on the desired level of hop exposure and extraction.

Hot break

The hot break is a natural occurrence that happens during the boiling process when proteins and other compounds in the wort coagulate and form visible clumps. This clumping or precipitation helps remove unwanted substances from the wort, resulting in a clearer and more stable beer. The hot break is typically observed as a foam or scum that rises to the surface of the boiling wort. Managing the hot break can be crucial for achieving a desirable final beer appearance and preventing unwanted off-flavors or haze.

Hydrometer

A hydrometer is a measurement tool used in brewing to determine the specific gravity of liquids, such as wort or beer. It consists of a weighted glass tube with a scale on the side and a calibrated stem. The hydrometer is floated in a sample of liquid, and the specific gravity is read where the liquid level intersects the scale. This measurement provides information about the gravity or sugar content of the liquid, which is essential for tracking fermentation progress, calculating alcohol content, and ensuring consistency in homebrewing.

I

Infusion

Infusion is a brewing technique that involves steeping specialty grains or adjuncts in hot water to extract flavors, colors, or fermentable sugars. This process is commonly used in extract or partial mash brewing, where the base malt is typically in the form of malt extract. Infusing the specialty grains or adjuncts creates a concentrated liquid known as wort, which serves as the foundation for brewing. The infusion temperature and duration can vary depending on the desired outcome, allowing for a wide range of flavor possibilities in homebrewing.

International Bitterness Units (IBU)

International Bitterness Units (IBU) is a measurement scale used in brewing to quantify the bitterness of beer, primarily determined by the hops used. The scale ranges from 0 to over 100, with higher numbers indicating a more bitter taste. The IBU value is determined by measuring the concentration of hop-bittering compounds, such as alpha acids, in the beer. Different beer styles have distinct ranges of IBUs, with hop-forward styles like IPAs often having higher IBU values, while lighter styles like lagers have lower IBUs.

J

Jockey Box

A cooling device that allows beer to be served at the perfect temperature directly from a keg, especially useful at outdoor events. It uses coils submerged in ice water to cool the beer as it travels from the keg to the tap, providing a portable and efficient way to serve large quantities of beer without electricity. Ideal for picnics, beach parties, and tailgating, the jockey box is a favorite among homebrewers for its convenience and effectiveness.

Juicing

In the context of homebrewing, juicing refers to the addition of fruit juices to beer to impart additional flavors, aromas, and sometimes color. This technique can be used at various stages of the brewing process but is most commonly added during secondary fermentation to avoid losing the delicate fruit flavors. Juicing is popular in the production of fruit beers, radlers, and shandies, offering a creative avenue for brewers to experiment with flavor profiles.

K

Kegging

The process of filling beer into kegs for carbonation and serving, bypassing traditional bottling to save time and effort. Kegged beer is carbonated by connecting the keg to a CO2 tank, allowing for precise control over carbonation levels. This method not only streamlines the packaging process but also reduces the risk of oxidation, maintaining the beer’s freshness and flavor integrity over time.

Kettle Souring

A brewing technique used to create sour beers by intentionally souring the wort in the brew kettle before fermentation. This method involves inoculating the wort with lactobacillus bacteria, holding the wort at a warm temperature to encourage souring, then boiling to kill the bacteria before proceeding with fermentation. Kettle souring allows brewers to produce sour beers in a shorter timeframe compared to traditional barrel aging and provides a controlled environment for souring.

Krausen

Krausen refers to the foamy layer of yeast and proteins that form on top of the fermenting beer during the active fermentation phase. It is a visible sign of vigorous fermentation and indicates that the yeast is converting the sugars in the wort into alcohol and carbon dioxide. The krausen can vary in size, texture, and color, depending on the yeast strain and fermentation conditions. It is important to allow the krausen to settle or subside before proceeding with steps like dry hopping, sampling, or transferring the beer to secondary fermentation vessels.

L

Lagering

The process of cold-fermenting and storing beer at near-freezing temperatures, is a method characteristic of lager production. This technique results in cleaner, crisper beer flavors by allowing yeast and particulate matter to settle out of the beer. Lagering periods can range from several weeks to several months, depending on the beer style and desired outcome.

Lautering

A vital step in the brewing process is where the mash is separated into the clear liquid wort and the spent grain. The process involves slowly draining the wort from the mash tun while rinsing the grains with hot water (sparging) to extract as many sugars as possible. Efficient lautering is crucial for maximizing the yield and efficiency of the brewing process, directly impacting the beer’s final gravity and strength.

M

Mashing

The initial step in brewing is where crushed grains are soaked in hot water to break down starches into fermentable sugars. This process is critical for determining the beer’s flavor, color, and body, as different temperatures and durations can influence the activity of enzymes in the malt. Mashing requires careful temperature control to optimize sugar extraction and set the stage for successful fermentation.

Mead

Although not a beer, mead is a popular fermentable among homebrewers, made by fermenting honey with water and often flavored with fruits, spices, or hops. Mead-making shares many techniques with homebrewing, including fermentation, aging, and bottling, making it an attractive venture for brewers looking to explore beyond traditional beers. Mead varies widely in sweetness, strength, and flavor, depending on the ingredients and fermentation process used.

N

Nitrogenation

The process of adding nitrogen gas to beer to achieve a smoother mouthfeel and a dense, creamy head, distinct from the sharper bite of carbon dioxide. Nitrogenated beers, such as stouts, are served under higher pressure through a restrictor plate, creating tiny bubbles that provide a unique textural experience. This technique is favored for styles where a silky mouthfeel enhances the overall drinking experience.

Noble Hops

A term denoting a group of traditional European hop varieties known for their mild, balanced aromatic, and bittering qualities. These hops, including varieties such as Saaz, Tettnang, Hallertau, and Spalt, are highly valued for brewing classic lager and ale styles, imparting subtle floral, spicy, and herbal notes to the beer. Noble hops are preferred for their ability to complement rather than dominate the malt profile of the beer.

O

Original Gravity (OG)

A measurement indicating the density of fermentable sugars in the wort before fermentation, providing an estimate of the potential alcohol content of the finished beer. OG is determined using a hydrometer or refractometer, and understanding this value is essential for recipe formulation and fermentation monitoring. A higher OG generally suggests a beer with a higher potential alcohol content and a more substantial body.

Oxidation

The chemical reaction that occurs when beer is exposed to oxygen, leading to off-flavors often described as stale, cardboard-like, or sherry-like. Oxidation can occur at several stages, including during transfer, bottling, or aging, making it critical for brewers to minimize oxygen exposure to preserve the beer’s intended flavors. Preventative measures include purging vessels with CO2, reducing headspace in packaging, and using antioxidants like ascorbic acid.

P

Pitching

The act of introducing yeast into the cooled wort to initiate fermentation is a critical juncture in the brewing process. The amount of yeast, its health, and the fermentation temperature are pivotal factors that influence the beer’s flavor, alcohol content, and clarity. Proper pitching practices ensure a robust and healthy fermentation, leading to a successful batch of beer.

Priming

The addition of a small amount of sugar to beer before bottling induces a secondary fermentation in the bottle, naturally carbonating the beer. Priming sugar can be added directly to each bottle or mixed into the beer before bottling to ensure even distribution. This method requires a precise calculation to achieve the desired carbonation level without risking over-carbonation or bottle explosion.

Q

Quaffable

Describes beers that are easy to drink, often light in body and flavor, making them suitable for consumption in larger quantities. Quaffable beers are appreciated for their balance and refreshment, ideal for social drinking or as session beers. The term emphasizes the drinkability and approachability of a beer, rather than its complexity or intensity.

Quarantine

In homebrewing, quarantine refers to the practice of isolating new or suspect beers to prevent potential contamination of other batches. This can involve separating equipment used for infected batches or keeping newly bottled beers away from others until confident no refermentation or bottle bombs occur. Quarantining helps manage risks and maintain the quality and safety of homebrewed beer.

R

Racking

The process of transferring beer from one vessel to another, such as from the primary fermenter to a secondary fermenter or from the fermenter to a bottling bucket, avoids the sediment at the bottom. Racking is performed to clarify the beer, aid in maturation, and reduce off-flavors that can result from prolonged contact with the trub. Careful racking can significantly enhance the final clarity and quality of the beer.

Reinheitsgebot

The German Beer Purity Law of 1516, originally stipulated that beer could only be made from water, barley, and hops. This law has historically influenced brewing practices in Germany and around the world, emphasizing the importance of simplicity and quality in ingredients. Though modern interpretations allow for more flexibility, the Reinheitsgebot remains a symbol of traditional brewing values and craftsmanship.

S

Sanitation

The practice of thoroughly cleaning and sterilizing brewing equipment to prevent infection and off-flavors caused by unwanted microorganisms. Sanitation is fundamental to brewing success, as even minor contamination can compromise the flavor and safety of the beer. Effective sanitation involves using chemical sanitizers on all equipment that comes into contact with the beer post-boil, ensuring a clean environment for fermentation.

Secondary Fermentation

A stage of fermentation occurs after the initial, or primary, fermentation, where beer is transferred to a new vessel to continue fermenting and maturing away from the majority of the sediment. Secondary fermentation is optional but can improve clarity, allow for flavor additions (such as dry hopping or fruit), and reduce off-flavors. This step, while not always necessary, can contribute to the complexity and finish of the beer.

T

Trub

The mixture of proteins, hop matter, and other solids that settle at the bottom of the fermenter during and after the boil, and again during fermentation. Trub removal is important for achieving a clear beer and preventing off-flavors, as excessive trub can lead to astringency and unwanted bitterness. Brewers often take steps to minimize trub transfer during racking and may use whirlpooling or filtering techniques post-boil to reduce trub volume.

Tun

A vessel used in brewing, such as a mash tun, where grains are mixed with hot water to extract fermentable sugars, or a lauter tun, designed for separating the wort from the spent grain. Tuns are essential components of the brewing process, each serving a specific purpose in preparing the wort for fermentation. Proper design and operation of tuns can significantly affect the efficiency and quality of the brewing process.

U

Unitank

A versatile fermentation vessel that can be used for both primary and secondary fermentation, as well as serving beer directly to consumers. Unitanks offer a streamlined approach to brewing by reducing the need for multiple vessels and transfers, minimizing the risk of oxidation and contamination. These tanks are equipped with features for temperature control, pressure regulation, and yeast collection, making them highly efficient for small to medium-sized breweries.

Ullage

The term refers to the space left empty above the liquid in a brewing vessel, keg, or bottle, which is filled with gas (usually air or CO2) to prevent oxidation and contamination. In kegging, ullage is critical for maintaining the right pressure and ensuring proper dispensing of beer. Managing ullage properly is important in packaging to minimize oxygen exposure and preserve the beer’s quality.

V

Vorlauf

A process in all-grain brewing where the wort is gently recirculated over the grain bed in the mash tun before lautering, helping to clarify the wort by filtering it through the grain itself. This step also helps to set the grain bed, acting as a natural filter during the sparge. Vorlauf contributes to the overall clarity and quality of the final beer by removing particulate matter early in the brewing process.

Vienna Lager

A style of lager beer that originated in Vienna, characterized by its amber to reddish-brown color, moderate hop bitterness, and toasty malt profile. Vienna lagers are brewed using Vienna malt, which gives the beer its distinct malt character and color. This beer style is known for its balance and drinkability, offering a harmonious blend of malt sweetness and hop bitterness.

W

Wort

The sweet liquid extracted from the mashing process contains the sugars that yeast will ferment into alcohol and CO2. Wort boiling is a critical step for sterilization, hop utilization, and flavor development. The quality and composition of the wort are fundamental to the beer’s final character, influencing everything from color and clarity to flavor and aroma.

Whirlpool

A process used after boiling the wort, where the wort is stirred vigorously to create a vortex, causing the trub and hop particles to collect in the center of the kettle, making them easier to separate from the clear wort. The whirlpool step also allows for the addition of late hop additions, extracting aroma and flavor compounds without contributing to bitterness. This technique improves the clarity and quality of the wort before it is cooled and transferred to the fermenter.

X

Xylose

A type of sugar derived from wood or straw, not typically fermentable by standard brewing yeasts, is often discussed in the context of biofuels more than brewing. However, some specialized yeast strains or enzymes can ferment xylose, allowing for the exploration of alternative ingredients and innovative brewing techniques. Xylose’s inclusion in brewing discussions highlights the ongoing search for sustainable and unique brewing materials.

Xanthohumol

A compound found in hops, known for its antioxidant properties, contributes to the health discussions around beer consumption. Xanthohumol is of interest for its potential benefits beyond brewing, including research into its effects on health and disease prevention. Its presence adds a layer of complexity to the role of hops in brewing, beyond flavor and aroma, pointing to the broader implications of ingredient choices in beer.

Y

Yeast

Microorganisms are essential for fermenting the sugars in the wort into alcohol and carbon dioxide, thereby transforming the wort into beer. Yeast selection is critical, as different strains impart distinct flavors and characteristics, influencing the beer’s profile. Managing yeast health and fermentation conditions is crucial for achieving the desired beer style, and ensuring a successful and consistent brewing process.

Yield

In brewing, yield refers to the efficiency with which the fermentable sugars are extracted from the grains during the mashing process, as well as the overall volume of beer produced. Higher yields are desirable, as they indicate a more efficient extraction of sugars and a greater amount of beer from a given amount of ingredients. Optimizing yield involves careful control of mashing conditions, grain selection, and process management.

Z

Zymurgy

The science of fermentation, encompasses all aspects of the brewing process, from the biochemical reactions of yeast to the practical techniques of beer production. Zymurgy is fundamental to understanding how different variables influence the outcome of the brewing process, allowing brewers to refine their craft. Enthusiasts and professionals alike delve into zymurgy to explore new brewing possibilities and to perfect the art of beer making.

Zwickelbier

A traditional German style, zwickelbier is an unfiltered lager that is sampled directly from the fermenter or conditioning tank, offering a fresh taste of the beer in its most natural state. This style is known for its cloudy appearance, smooth mouthfeel, and the presence of yeast, providing a unique flavor profile that’s richer and more complex. Zwickelbier celebrates the brewing process by allowing consumers to taste the beer before it undergoes final filtration and packaging.

This homebrewing glossary will be updated on an ongoing basis. Send us a message with any suggestions you may have.

© 2024 by brew.info. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission of brew.info.